Methinks he talketh too much: Non-verbal communication skills explored, with help from Woody Allen and Diane Keaton, William Blake and a mystery actress.

Date posted: Sunday 15th September 2013

You start a conversation, you can’t even finish it.

You’re talkin’ a lot, but you’re not sayin’ anything.

From Psycho Killer by Talking Heads

I had a strange encounter in a kitchen at a party once. I was at drama school, studying Speech Therapy, and got into conversation with a student who was later to become a very famous actress. Now to help us visualize the conversation fully I’m going to use the technique devised by Woody Allen in his film Annie Hall. Woody’s character has just met Annie Hall, played by Diane Keaton, and is acting cool and trying to hide his huge desires for her. As you will see from the YouTube clip, they are both talking pretentious garbage, while the subtitles show what is really going through their minds.

I’m at the party and a bit bored. There are mainly drama students there, and I’m the only Speech Therapist, so we have nothing really in common. I head into the kitchen to see if there’s any beer left in the Watney’s Party Seven (for it was 1979). I was in the process of trying to decide why the beer tasted so strange .Was this its normal flavour, or had a reveller dumped a fag end in there? In walks someone who I was later to see in The Horse Whisperer, Four Weddings and a Funeral, The English Patient, I’ve Loved You So Long and any number of French feature films. I had been aware of this very attractive girl for some time, but had never thought that the person I was beginning to worship from afar would actually speak to me. Let’s call her Annie:

M: Hi, would you like some delicious English beer?

(What am I doing? This stuff is poisonous.)

A: Are you an actor?

M: Sort of. I’m a Speech Therapist, but underneath we’re all actors, aren’t we?

(What am I saying? This is the end of the beginning.)

A: Actors are so boring. They spend all their time talking: endlessly going on about themselves and the project they are working on that’s going to make their name.

M: Yes, I know what you mean. Speech Therapists are just the same.

(No they are not. They are members of the most wonderful profession. Is that a cock crowing three times?)

A: Tell me something. I’ve always wondered how children learn to talk. Can you explain how they do it?

M: It’s quite simple really. The Behaviourists originally thought children learned to talk by imitating adults and being rewarded for doing so. Noam Chomsky recently wrote an amazing book, where he outlined the possibility that children actually generate their own rules of grammar…)

(I’m boring myself. Why is she listening to this?)

[In the next room anyone with any social life is dancing to Psycho Killer by Talking Heads]

Fifteen minutes later Annie stopped me and said something beautiful:

A: You know, you remind me of William Blake.

M: Do you mean the visionary painter and poet, who wrote Songs of Innocence and of Experience?

A: That’s the one!

M: The one who wrote

To see a world in a grain of sand

And a heaven in a wild flower,

Hold infinity in the palm of your hand,

And eternity in an hour.?

A: The very same.

M: I’m flattered. Is it because I am a bit of a visionary?

A: No. It’s because listening to you makes a quarter of an hour seem like eternity. (Exit Annie)

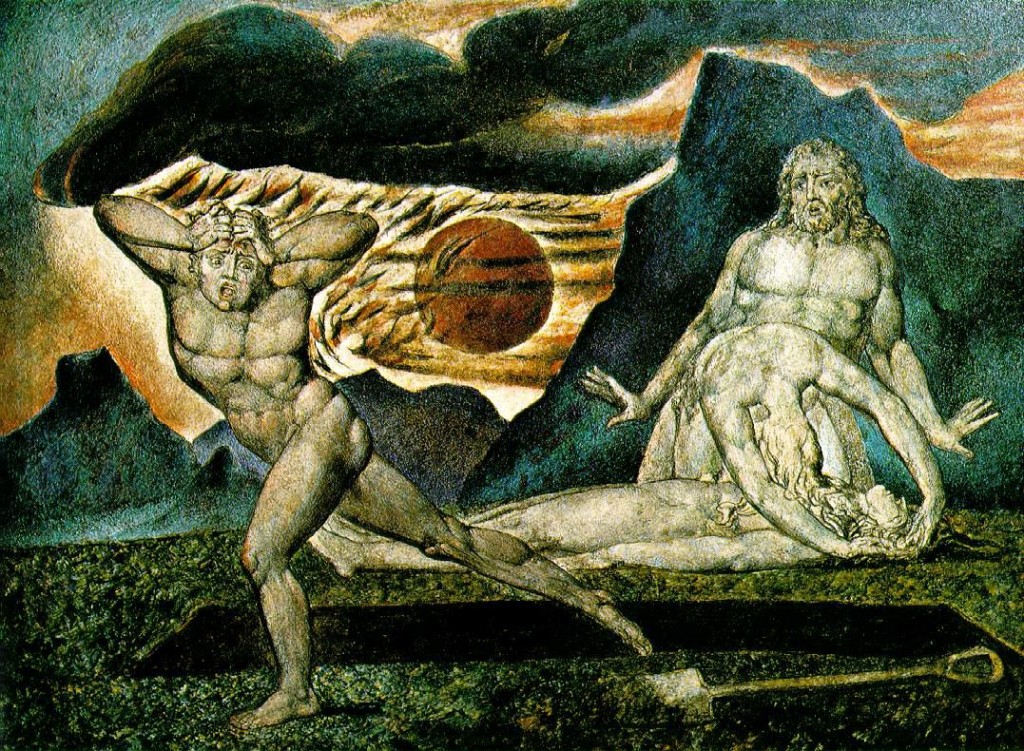

William Blake: visionary or ’chatterbox’?

I saw Annie a few days later in college, and she made a point of buying me a coffee and offering me a cigarette (it was 1979). I tried very hard to look bruised and hurt after her crushing put down. She explained that she hadn’t meant to be rude, but was fed up with dull, egocentric actors trying to hit on her. She had come up with this classic put down, wanted to try it out on me first, to see if it would work. It transpired that it was useless: the only thing that can deflate an actor’s ego is a negative review. As it turned out, I had the same problem as her (being constantly hit on, that is), so we struck up and maintained what is known as a ‘friendly rapport’, until she left the course abruptly, to emerge a few years later as an internationally respected actress.

What I discovered, and what this piece is all about, was that Annie had a big interest in non-verbal communication. She was particularly fascinated by how we read , or in some cases fail to read, the subtle clues that speakers and listeners give each other in conversations. When I tell teachers that I have a special interest in children who are very quiet, they often joke, “Can you help us to stop some of the children talking: they are real chatterboxes?”

This is not as flippant a question as it seems. Like Annie, we have all met adults who just do not seem to sense that they should stop talking. This can be such a problem that we hide when we see them coming down the street, or avoid eye contact with them if they share the same office or staff room as us. They seem to have a compulsion to talk, or invariably turn every conversation towards their favourite subject, and then launch into a monologue that seems to be unstoppable. They go on interminably: no matter what non-verbal cues we give off; e.g. looking over their shoulder; glancing at your watch; making hints such as. ‘I guess you have lots of work to do/I’d better let you go/ I’m just on my way out/Do you have the time?) It seems that the compulsive talker does not understand hints.

I see conversation as a kind of a dance. Some find it natural and very quickly become really skilled at the dance of conversation, while most of us need to practice the steps. With a lot of positive experience we can do very well. That is until we are faced with someone who doesn’t know, or refuses to follow, the dance, and then we become anxious and things start to fall apart. At the party I was overawed by Annie, so became anxious and began to talk gibberish. That’s a natural reaction: especially when alcohol is involved. However talking too much, and being unaware that you do so, can be an indicator of a difficulty with non-verbal communication: not being able to ‘read’ other people.

One of the features of Asperger syndrome is a chronic inability to read other people’s signals. This can manifest itself in children and adults ‘buttonholing’ people and launching into monologues about their favourite subject. This can be exacerbated when the person with Asperger’s feels anxious. Now I’m not suggesting that your colleague with ‘verbal diarrhoea’ is ‘on the spectrum’, though people may joke about this behind his back. It may be that they are anxious about talking. This anxiety may be caused by a lack of understanding of non-verbal communication.

I used to think that such difficulties were out of my remit, but recently I met Communication/Behaviour Specialist Sioban Boyce, who convinced me that children and teenagers with social and behavioural difficulties are likely to experience problems with non-verbal communication. These youngsters can not only be identified, but can be helped to communicate more effectively. In her book Not Just Talking: identifying non-verbal communication difficulties- A life changing approach Sioban describes the development of non-verbal communication in infancy. This particularly focuses on babies being able to look at their carer’s face, and beginning to interpret emotions and language through ‘reading’ facial expressions and adults’ tone of voice.

I often hear adults who talk too much, and almost exclusively about their particular interests, being described as being ‘on the spectrum’. I often hear it suggested that to find out why a particular child is heading towards a diagnosis of ASD, you only have to observe the father’s behaviour to see a possibly inherited pattern. In other words, ‘the dad’s a bit of an extreme geek/nerd/anorak (you choose your pejorative label), so it’s no wonder that his child is showing signs of autism.’ But could it just be possible, just possible, that some of these parents and some of these children will benefit from someone assessing their non-verbal understanding, and helping improve their awareness and skills? Might then their anxiety in social situations reduce, so that they can then develop appropriate social and conversation skills?

I think so.

Not Just Talking: identifying non-verbal communication difficulties- A life changing approach by Sioban Boyce is available from Speechmark. Visit www.notjusttalking.co.uk or http://www.speechmark.net/not-just-talking-15012 for more information.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=j4xoxFrRA2Q

Sign up for Michael's weekly blog post by clicking here!

Leave a Reply