The Beatles: their role in my downfall: or why maths is (or isn’t) so much fun. With help from John, Paul, George and Ringo and Dirk, Stig, Ron and Barry from The Rutles!

Date posted: Thursday 16th January 2014

Ooh I need your love babe

Eight days a week.

Eight Days a Week by The Beatles

The Fab Four |

The Prefab Four |

You may love The Beatles. You may think, ‘They are OK I suppose, but my dad preferred The Stones’. You may be someone who hates The Beatles. It’s just possible you may have no idea who The Beatles were. So here’s a warning: Prepare for a Beatlesfest!

I’m not going to moan any more about having severe difficulties with maths. I just am not very good with numbers, and I’ve got used to it. But the rot had to set in somewhere, and my earliest memory of not having a clue what a teacher was talking about was when I was in Year 1, aged five. The teacher showed us how to ‘take away’. She wrote

21

– 8

on the board and showed us how to ’borrow one and then pay it back and make sure you keep your numbers in the right columns’ and stuff like that.

I think she was a student, because she was very nice to us, and kissed me once because I said, “Your ‘discovery table’ with the little pot of iron filings and the magnet we can play with is just the most exciting thing and I wish you were my big sister or even my mum and can I hold your hand at playtime Miss?” and all the things little boys say when they are clearly in love with their teacher. Come to think of it, I’m sure she was definitely a student because once she took us for a PE lesson in the playground, all about hoops and balls, and got told off by the headmaster for changing into her black mini sports skirt in front of us children and a group of postmen from the depot next door. (Who got a good talking to by the headmaster for disrupting the lesson with their wolf whistling at Miss).

I don’t hold a grudge against that student teacher, but ever since then when I have to do mental subtraction I clearly visualise the way that sum was laid out on the board. As a result I have never been able to play darts, do measurement properly, and other important things like that. I’m not bitter, I just have dyscalculia. However I do get a bit peeved when people with an innate ability to do complex maths say things like, “You haven’t got dyscalculia. You must have had a bad experience when you were a child, which put you off maths.” In the same way some people who are naturally musical say, “Everyone is musical and no one is tone deaf.”

Sorry, some people just can’t hold a tune, and it doesn’t matter how much you teach them, people will still cringe when they sing. However, if they enjoy singing and aren’t made to feel self-conscious about their relative lack of skill, then most listeners will be pleased for the efforts that they make and the obvious pleasure they are getting from joining in. And if someone is really struggling to understand music, but in spite of this makes an enormous effort to master a few basic tunes on the piano, then they should be admired for their tenacity and determination to do their best.

What’s my point? Am I saying that people with dyscalculia and dyslexia shouldn’t be taught maths or to read and write? Not at all. What I am saying is that everyone should be taught well. Some children pick up new maths concepts very quickly, while others need a lot of support and guidance. For some children, everything the maths teacher says seems to make sense, while for others, like me, it just sounds like white noise.

Are you picking up an emotional tone to this post? It’s there because learning is an emotional activity. Learning in school is extra emotional because you do your learning (or failing to learn) in public. Which brings me to The Beatles. I had an operation when I was nine years old, and was in hospital for a week. I had a visit from the hospital teacher, who asked me what I would like to play with, to cheer me up and make me feel better. Later in the day she popped in with a small pot of iron filings and a magnet. She could see that I was delighted, but I unwisely asked her if we were going to have PE next, with hoops and balls.

Obviously she couldn’t see where that question came from, and looked a bit alarmed. The next day a psychologist paid me a visit. Maybe she thought that by removing a boy’s appendix you could damage the maths part of his brain, because she asked me loads of maths questions: including if I knew what day of the week it was, and what day came next. Quite honestly I was a bit disoriented and wasn’t sure, so made a wild guess. I could tell that I had guessed wrong because she asked me lots more questions, including how many days there are in a week. Maybe I was on morphine, but an image came into my head of The Beatles singing Eight Days a Week. So I said ‘eight’.

The Beatles: Eight Days a Week

I don’t know what kind of impression I had made on the psychologist, because the next day the teacher left me an exercise book with squared paper and a lot of sums and ‘problems’ written inside. My heart sank. The first page had lots of easy sums, and a little message that said, “Please help John (the boy in the next bed with the broken leg) to check that you have got the right answers.’ The problem was quite tricky, ‘Your mum brings you a tin of sweets and asks you to share them out equally between the 15 children on the ward. There are 56 sweets in the tin. How many will you have each and how many will be left over?’ There was a final problem: ‘Ask all the children and staff on the ward (including the cleaners and the doctors who come and see you on the ward round) what their favourite drink is, and find a way of showing this by drawing a picture (see*for the results!).

As you can imagine, I had great fun with all three tasks and was cheered up no end and felt a lot better. That teacher and psychologist were inspired, and not only made me feel emotionally and physically better, but helped me to understand that maths can be great fun, as long as the people teaching it are helpful and imaginative.

I was off school for a month, and by the time I returned the class had been taught long division. One thing I learned while being away is this – never be ill, because you will never catch up on what you have missed. I never understood long division.

Shortly afterwards we moved house and I started at a new school. The head teacher liked to assess new children’s skills himself. Unluckily for me, his first question was about long division. When the head could see that I had no idea how to do sums like that he said, “Didn’t they teach you any maths in Essex? I think you’d better have your maths lessons in Remove.” In Remove, which was a special classroom for children with problems, I learned that there is such a thing as dyslexia, or ‘Word Blindness’ as it was called in 1967. My friend Kevin was word blind and spent most of his day in Remove. Oddly enough he knew the lyrics to all of The Beatles’ hits, could sing in tune and learned to play the piano very well ‘by ear’. That wasn’t enough to get him a ticket to ride out of Remove though.

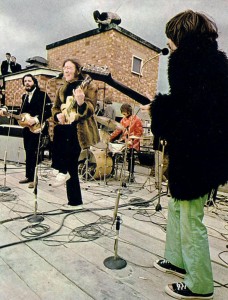

The Prefab Four playing on the roof: the coolest rock event never?

Rooftop full concert: the real thing

Let’s push The Beatles theme just a little bit more. I used to get a bit defensive about not understanding maths. Some teenage boys can be a bit nasty to other boys who they sense have a weakness. So when other kids used to scornfully ask me, “Surely you can do algebra? It’s easy!” or “How can you not like maths? It’s a great subject!” I used to say, “How can you not know the lyrics to I Am The Walrus and Strawberry Fields Forever? My friend with word blindness does. And how can you not like The Beatles? They are a great band!” The Beatles debate still goes on, as we can see from the responses of the American children in the clip.

What do kids today think about The Beatles? Luckily some things never change.

There is a big irony about me that is not lost on many people (including myself). How can someone who admits he is appalling at maths have the nerve to write a book on the subject?

Well I have always felt that people should really believe that the key to understanding maths is to accept that it is a second language. Mathematics is all about language. If I could have understood the meaning of the words, and if someone had taken the time to explain the practical importance of algebra and trigonometry, for example, then maybe it would have made more sense. I now know that understanding about number and calculation is important, but there are so many other aspects of maths that we can learn in a fun, interesting and meaningful way. We also need to begin with what the child already knows and build on their knowledge.

My colleague and co-author Judith Twani has always believed that children naturally talk about the maths that is all around them, but unfortunately learn to associate the subject of mathematics with knowing mainly about numbers and calculating. This can put many children off learning about maths from a very early age. Perhaps more than any other aspect of learning, a fear of maths can last a lifetime. Now that I work with very young children, I can see just how important it is to make sure that we build on their existing knowledge, and to talk about the maths that is all around them: through everyday activities and as they are playing.

This is why our book is all about talking naturally with children during everyday activities and as they play, so that they can make sense and have fun with mathematics from very early in life.

You can read about it here:

http://www.lawrenceeducational.co.uk/shop/product_info.php?cPath=34&products_id=306

And as The Beatles sang, all you need is…

* The ward children and staff drinks survey results

Children:

- Most popular: Coca Cola (a huge luxury in those days, and banned from the ward).

- Least popular: Lucozade (‘Nasty orange stuff’ and encouraged on the ward).

Staff:

- Most popular: shampane and ginis (it’s good for you)

- Others: wisky, Jack Daniels (who I thought was a Spurs player), Bourbon (I thought that was a chocolate biscuit), Tia Maria and Matron’s favourite, ‘a nice cup of tea… followed by a large glass of Sanatogen’ (‘It fortifies the over forties.’)

Take care out there

Michael

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=j4xoxFrRA2Q

Sign up for Michael's weekly blog post by clicking here!

I was laughing out loud, and also empathised with a lot of what was said, your young memory is fantastic and helps put things into context for you…and for us, thank you once again for an insightful blog, which I will pass on.

Thank you Eileen! I think that any small kindness goes a long way to wiping out the impact of unpleasant experiences. We had a teacher who used to say, “Hello everyone, it’s nice to see you all again” at the beginning of every lesson. I think he meant it, because we all thought it was a nice thing to do. When I was a teacher that was how I started every day with my classes.

Very best wishes

Michael

Snap. I’ve also just written a maths book – well, two actually! Most maths books are written by people who are good at maths and have little idea about what it feels like to languish in the lower sets. Good teaching should inspire but we also get ourselves horribly wound up nowadays about ‘understanding’. Understanding a process can be much more difficult than doing it: driving is an excellent example of this.

My goodness Michael, you certainly went through the mill as a child. I made a promise when I was about eight that I would never, ever forget what it felt like to be a child. I hope I’ve clung onto that promise half as well as you have.

Thanks for another entertaining blog.

Thanks John! I’m looking forward to finding out more about what you have written!

Very best wishes

Michael

Maths Sharpener Books – trying to add some fun to the new curriculum. Tada:

http://www.badgerlearning.co.uk/ecommerce/primary-resources/maths/

If maths is a second language is it possible to apply the same criteria to chemistry. I don’t know how many chemistry lessons I sat through in the 60’s but the teacher might as well have been communicating in a foreign language. What on earth did all those symbols mean? And why, after spending hours in a smelly lab messing about with bunson burners did those symbols change? However, I do believe it is possible for a person to be tone deaf and have no sense of rhythm as I have been married to him for over 30 years.

Hello Carol

You are so right… the number one thing all subject teachers need to do is introduce the vocabulary of the subject. I worked with a brilliant art teacher who had all the key words of the subject hung up from the ceiling, so that everyone visiting the department (including support teachers like me) would know what we were talking about. This had a big impact on the students, who were able to talk with confidence about art, as well as try to paint and draw using the same techniques.

There is a big debate amongst music and dance teachers about ‘tone deafness’ and lack of rhythm. I think its an area worth exploring.

More soon!

Michael

Note form sorry

“Michael your lack of Maths expertise is clearly linked to your feelings about your student teacher”.S Freud

Everybody is not musical but everybody has a (singing) voice somewhere in them….is something I almost 100% believe.

I hate to admit it but I am very probably dyscalculic but I am also a musician (of sorts) BUT I believe a lot of music is maths…patterns etc. I would be abetter musician if I understood maths concepts more, I am sure.

My handwriting is terrible and I cannot draw anything to look like anything at all and I have often wondered what part of that is inherited/innate or whatever. I do know however that in my infant class aged 6(maybe) me and Trevor Early were sat out the front specially to practice our letters on that funny lined paper (what was that method called? I keep wanting to say Elizabeth David but that’s not it) and told we would receive a smack if we did another “double loop.” The problem was, I didn’t know what a “double loop” was, consequently I was unaware if I was about to produce one or not. For the record, I still don’t know what a “double loop” is. Jah bless Mrs Taylor and Mrs Shaw, they weren’t nasty, just ill informed I think.

John Rice: YES! you are so right Maths tuition books should be written by people who find Maths difficult not by Maths experts unless said experts can pass some sort of empathy test

Bit late but re the post about Dutch speakers if you do nothing else today search youtube for Steve McClaren (English Mancunian football manager) managing a Dutch football team, being interviewed by Dutch Telly about his team’s chances in the champions league. Once you have stopped laughing and (frankly)mocking, try and fathom why some (English) people feel that they will be better understood by a non English speaking person by speaking to that person in English, but with the accent that the non English speaking person might be expected to speak English with( are you still with me?)It’s a classic variation on the speak loudly and slowly at foreigners trick. If you are ever with an English person who attempts either of these techniques, walk away rapidly they don’t seem to know they are doing it and it can only get worse.

Peace and love

Tim

Hi Tim!

Some fantastic points there!

I believe you may have fallen victim to an adherent of Rosemary Sassoon. There was a statue dedicated to her in the lobby of the London Institute of Education. It was of a little girl writing in a handwriting book. I couldn’t be exactly sure if she was doing a double loop or not, but I guess not as there was no look of confusion/fear on the little girl’s face.

Everyone is capable of making music of some sort (why else would we believe in music therapy?) but maybe it’s not always music to everyone else’s ears.

Now your Steve McLaren comments are quite fascinating. I’ve watched the You Tube clip, and he is doing something very funny, but also very interesting. he may not realise what he is doing. It seems quite barmy, but there has been some research that suggests that if you are in a foreign country and talk to the locals in the same way that they would talk to you (accent, inflections, warped grammar and gestures) then they will understand you better.

I am not going to go round to my French neighbours and start talking like Rene from ‘Allo ‘Allo, but I know someone whose mother does this every time she visits France and she seems to do very well.

The big queshtion for Big Shteve is whether it makesh him more popular with the Dutch playersh and media than when he wash England manager?

All the best

Michael