Do babies need mothers? In memory of Professor Hazel Dewart. With help from Bob Marley, Bobby McFerrin and Playing for Change

Date posted: Friday 27th March 2015

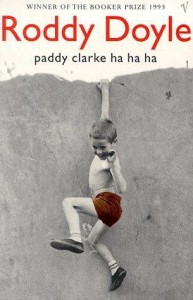

When I was nine years old I told a lie, in the hope that I would be allowed to take a day off school. My lie was so successful that I was off school for a month. Unfortunately the first week of that month was spent in hospital having an operation, and the following three weeks recovering from septicaemia. Looking back on it, I think I was what would now be described as ‘troubled’. But in those days (1966) I was variously described by teachers as ‘naughty’, ‘downright disobedient’, or ‘a bit of a pickle’, depending on how sympathetic they were. I was an avid reader of The Beano and The Dandy, and Dennis the Menace, Roger the Dodger, Minnie the Minx and The Bash Street Kids were my main role models. So lying to my teachers and parents, to avoid trouble and going to school, had become second nature. I have recently read Roddy Doyle’s brilliant Paddy Clarke Ha Ha Ha and can totally identify with little 10-year old Paddy.

It all started when I hadn’t done a poo for three days, which gave me a bit of a stomach ache. I was always complaining of headaches and various pains, but my parents, being of the ‘Go to school and if you are really ill the staff will call us’ variety, never believed me. (Maybe it was their medical backgrounds that gave them the uncanny ability to spot a malingerer like me from 100 yards?) So I was sure that finally having a bone fide symptom would be the ticket to a few days hanging around at home. However, I was a bit unsure about how to describe my visits to the toilet, so when my mum asked me, ‘Have you done a poo recently?’ of course I immediately piped up, ‘Yes!! Lots!!’

Then I made a second very big mistake. When my dad asked me, ‘Where does it hurt?’ I had meant to point to my stomach. Unfortunately I hadn’t been taught any human biology, so waved vaguely in the direction of the right side of what I now know is described as the ‘lower abdomen.’ Bad move. You may know that a pain in that area must mean that you are in imminent danger of dying of appendicitis, so before I could say, ‘Honestly, I think I’m feeling better now’ I was being examined internally by a GP. (They didn’t wear gloves in those days, and how sticking a thumb ‘up the back passage’ leads to a differential diagnosis of an inflamed appendix is still beyond me.) The next thing I knew, the priest had been sent for, and I was taking Holy Communion in my pyjamas, while he intoned what sounded ominously like the Last Rites. The ensuing seven days are etched in my memory. Waking up to see a consultant and a gaggle of medical students inspecting me ‘down there’, nasty injections of penicillin, a baby in the ward with a fractured skull and the schoolboy in a private room lying very still with tubes attached to him (he’d been knocked down by a car). It was all a bit of a nightmare.

And no one believed that I was in agony and couldn’t stand up, let alone walk. It especially hurt when I laughed, so the nurses suggested I wrote a sign saying ‘Don’t make Michael laugh’ and stuck it above my bed. Trust me to have a boy in the bed opposite with ‘word blindness’ who couldn’t read the word ‘don’t’ and had an endless supply of hilarious ‘knock knock’ jokes.

The nurses were lovely, and fair play to my parents, they visited me every day, and gave me a bottle of Lucozade. But my biggest anxiety centred on the girl in the bed next to me. She never got any visitors and cried softly in the night. We talked a lot, but she was a bit vague about why she was in hospital. She hadn’t had an operation, and described herself as being there for something she mysteriously described as ‘observations’. As the days passed by, I must confess that I began to hold a torch for Emily (she liked to read in the night when she couldn’t get to sleep, so I held a miniature flashlight my mum gave me to play with, while we both read The Beano until the nurses came and gently told us off.)

Us children found lots of different ways to get the lovely nurses to visit our bedsides, and to keep them there for as long as possible. Emily’s ruse was to always complain that something new was wrong with her. Unfortunately, the more she complained the fewer visits she got from the kindly nurses. We both benefited from having one particular nurse giving us a kiss goodnight and tucking us in. As I became more and more sick from infection and chronic constipation, (the operation had not been a success in that department), I found I couldn’t sleep. To my little mind, what I needed was more kisses and hugs from the nurses, so I pushed off my bedcovers and lay on my back with one arm outstretched and my eyes firmly closed, feigning sleep/death. (I’d seen an actor with malaria ‘dying’ on TV in much the same way). Lo and behold, along came nursie to tuck me in, give me a kiss and stroke my hair until I dramatically fluttered my eyes open and pretended to talk deliriously in my sleep.

Emily was busy watching and did the same thing half an hour later, and got the same treatment. The day before I was discharged, Emily finally got a visitor. It was a man who sat there for all of 10 minutes, kept his coat on, and rushed off without giving Emily a kiss. As he hurried away from the ward I overheard two nurses saying to each other, ‘That’s the father. There’s your problem.’

I eventually made a full recovery, though my psychotherapist tells me that I have been ‘emotionally traumatized and scarred’ by my experience in hospital. (Maybe I shouldn’t have shown her the huge livid scar that I carry to this day, but she did ask to see it.) But if I’m scarred, then what about poor Emily, with her mystery illnesses and father who didn’t know how to talk her and couldn’t be bothered to take his coat off?

Where is this all going? Well, I forgot about my hospitalization until I was 21, when I was in my first year of studying to become a speech therapist. My favourite lectures were developmental psychology, due, in large part, to our lecturer, Dr Hazel Dewart. Hazel had recently completed her doctorate, and we were her first students. I have never met someone so nervous about teaching. Her first lectures were absolutely excruciating. They were beautifully prepared, down to her handwritten handouts with their superb written explanations. Unfortunately, she found it almost impossible to explain anything verbally, because of her chronic nerves.

This was in the Central School of Speech and Drama, and every lecture room had a piano in it. The college principal must have believed in the old adage that ‘a closed piano is an unplayed piano’ because the lid of the piano in our lecture room had been surgically removed. Half way through a lecture on Attachment Theory, Hazel got up and started slowly walking backwards as she spoke. We could all see that she was heading for the piano. “And so…erm… Bowlby…erm… wrote that… erm PLONK!!!!! ‘Oh my God!!! I didn’t know the lid was off the piano!” (Hazel had just sat on it.)

Later in the week Hazel was leading several of us students in our first seminar. It was in a small room at the top of the building overlooking the roof of the town house next door. Hazel began our discussion,”Erm…we are thinking about babies and young…erm children and their…erm OH MY GOD!!! THERE’S A RAT IN THAT GUTTER!!!” And she raced out of the room. She came back soon afterwards, looking shaken and stirred. “I can’t stand rats. It was a standing joke at my uni that I was the only psychology student who refused to observe rats and conduct those stupid experiments where we had to put them in mazes…”

Central School of Speech and Drama

After that, Hazel’s nerves improved, and I hung on her every word. We all looked forward to seeing what lovely new dress and cool shoes she would wear at the beginning of each week. I was thrilled when I discovered that Hazel was coming to observe me at a placement at a playgroup in Hackney. We spent pretty much the whole session painting and sharing books with Nigerian and Turkish children. Hazel gave me a lift back to college, and as we were driving towards Finsbury Park she asked me, a propos of nothing, about my beard. I told her that sometimes I had the urge to be clean shaven. Hazel posed a question that has stayed with me ever since, and always makes me smile: “When was the last time you had it off?”

“Well,” I replied without thinking, “I’m often tempted to do it on a Sunday evening, but I’ve asked some of the girls on the course what they think, and they’ve told me not to bother.” I have a memory of trying to stifle the giggles all the way back to our college in Swiss Cottage. I was also thinking about how wonderfully human Hazel was, considering she was a psychologist. Looking back on it, I wonder if that silly conversation was the germ that led her to write The Pragmatic Profile of Early Communication Skills and the later Pragmatics Profile of Everyday Communication Skills in Children. These became the seminal works on pragmatic development in children (how we convey meanings through talking and through understanding non-verbal signals, so that we can communicate subtle meanings and go on, for example, to understand jokes, including innuendo).

Playing for Change: Don’t worry, be happy

But what I most remember about Hazel, and am eternally grateful to her for, is getting me fascinated by developmental psychology. I can still picture her describing the work of Schaffer and Emerson and Michael Rutter’s Maternal Deprivation Reassessed and posing the big question, ‘Do babies need mothers?’ I will never forget her showing us a film about the work of psychoanalyst Dr James Robertson, exploring how young children in hospitals in the 1960s were routinely left in cots, and how parental visits were not seen as important, or even discouraged. His observations of toddlers sitting alone in cots initially screaming for their parents, but over the days gradually giving way to utter despair and finally becoming silent and detached from their parents, were groundbreaking. They led to major changes in the care of children in hospitals, and particularly allowing parents to stay with their sick children for as long as they liked.

Warning! This short extract from Dr James Robertson’s film is highly disturbing.

We were all deeply moved while watching these films, but I don’t think any of us had expected Hazel’s reaction to one particular scene from a film she was showing us. A parent finally visits a poor little girl, who has become almost catatonic. It’s her father, and he stays for five minutes and doesn’t take his coat off. Throughout the brief visit he doesn’t touch his daughter once, and she ignores him.

Hazel suddenly left the room. When she returned she had clearly been quite upset. “I’m really sorry”, she apologized, “I can never watch that particular scene. That insensitive man didn’t even take his coat off!”

How could you not love a lecturer as sensitive as that? Sadly, we didn’t have Hazel for psychology after that term, and our subsequent lecturer was more, how can I put it, ‘cerebral’. I was thrilled when, four years later, Hazel came to visit my language unit, to observe me working with young children with severe speech and language delay. She was researching for her ground breaking book. I met her only once after that, as she was coming up the escalator at Warren Street tube station, “Oh hello Michael!” she greeted me with her beautiful Northern Ireland accent. (She remembered me!!) I’m on my way to Westminster University, as I’ve just been given a chair there.”

I nodded sagely, but was puzzled by why she should tell me about going to collect an item of furniture. I never saw Hazel again, and have been terribly saddened to hear that she died recently, from cancer. She had a huge influence on me, and today, which is the first day of my retirement, I’m sitting on the ferry in the middle of The Channel, looking at the sun shining on the sea and thinking about how academics like Hazel can be so inspirational, and have the chance to have a hugely positive impact on other people’s lives.

Playing for Change One Love

I’m sorry that I never got to tell Hazel how brilliant she was. I don’t know if she liked reggae, but seeing how she lived in Stockwell for a long time, I imagine that West Indian culture must have been buzzing around in her subconscious somewhere. Bob Marley was known to have spent quite a bit of time in the area before he became famous with the Wailers, and when he was in self-imposed exile after the attempt on his life in Jamaica. So I’d like to dedicate these songs by Playing For Change to Hazel.

And do babies need mothers? I asked Hazel about this just before she went off on maternity leave with her first baby: ”Well Michael, from an academic viewpoint you’d have to argue about it, but personally I think it’s a bit of a stupid question.” Now I’ve finally written my own book, which naturally references Hazel’s and Susie Summers’ work on pragmatics, it seems only right to dedicate the book to her. Thanks Hazel.

Take care out there

Michael

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=j4xoxFrRA2Q

Sign up for Michael's weekly blog post by clicking here!

This brought back so many memories Michael. Hazel was one of the good guys. I remember her shyness and nervousness. I remember your beard too! Thank you for the article – it was so good. You write terrifically well. And you’re retired? Really. I’m still struggling on!! Josephine x

Hi Josephine! And to think I only had it off once during my three years at Central (my beard)!

Simply beautiful Michael. I want to write so much but am too moved! I just hope Emily found happiness…….

Thank you Mine! Fortunately hospital care of children has moved forwards so much. You have to hope that children like Emily will get help when they are adults so that they can undo for themselves some of the harm inflicted on them by parents who have themselves got ‘unmet needs’.

Hazel Dewart was great for me because she was so ‘human’ in the sense that she wanted us to look at little children as sensitive beings, as opposed to fascinating specimens to rote learn about their stages of Piagetian development. (We had that too, but Hazel made sure that it was all grounded in thinking about babies and toddlers having emotional needs first and foremost.) It’s very sad that she is no longer with us, but you’d hope that there are lots of developmental psychologists who are as ‘feeling’ as Hazel.

Best wishes

Michael

Michael,

As Hazel’s husband, I got only her version of events at Central and I don’t remember her telling me about the rat incident – although, given we had moved into what had been a derelict building in 1978 and were still doing it up when our first two children were born in 1980 and 1982, she might not have wanted to admit that her anxieties about the building extended beyond having nightmares about dry rot (true!) which was in the building and which we had had to eradicate.

I ought to be fair to Hazel apropos your tale of her obtaining a chair at Westminster. She moved there from Central as a senior lecturer but then obtained quite shortly afterwards the position of head of the Psychology Department, which I recall being described as Chair of the Department, a description that raised expectations that the incumbent would be a Professor. However, she was not appointed Professor until some years later.

I never knew Hazel had come across as a nervous first time lecturer to her students although I knew she was always anxious to ensure she was well prepared. The only feedback I had (why do I call it “feedback”? I had no expectation as the spouse of a lecturer to any information on how well or otherwise she was doing) was from Elaine, the head of the Speech Therapy Department at Central, who told me that Hazel was a natural teacher. But I know she was very fond of that first cohort at Central and I knew of your existence as the only guy in the year – and, having thought at the time you occupied an enviable position, am very sorry that you only once had it off during your time at Central!

But thank you for your appreciation of Hazel.

Hi Paul

I’m delighted that you took the time to comment on my post. Hazel was an inspirational teacher and, as you can see, had a lasting influence on me. My book, Talking and Learning With Young Children, is dedicated to her.

Very best wishes

Michael

Thanks Michael for your lovely memories. I too remember Hazel from my time at Central (a little after you I suspect). I kept in touch with Hazel and she kindly sent me some material. Would you be able to pass on my details to her husband Paul? Cheers

Andy

Hi Andy! Thanks for getting in touch. I passed on your info. Hazel had a very big influence on me, and my fascination with infancy and early years began with her lectures. It’s hard to put into words really, but she came to visit my language unit once, and I was just thrilled that she had chosen to come and see me at work. She was always very positive an complimentary and had such interesting things to say about children.

Best wishes

Michael